Over the last month we’ve spent a lot of time in northern India, especially in the cities of Leh (in Ladakh) and McLeod Ganj (in Himachal Pradesh). These areas are home to many thousands of Tibetan refugees who escaped persecution by the Chinese and have been granted asylum in India.

China began to send people into Tibet in 1949, soon after the World War II, under the guise of providing assistance to this remote nation. Until this time Tibet was a sovereign mountain kingdom, whose geography and leadership kept it generally isolated from the rest of the world. Tibet was politically naïve and accepted Chinese assistance grudgingly until it became obvious that China had intentions to colonize. For China, the country of Tibet was a huge new land area rich in mineral resources into which they could expand. Tibet was hopelessly unequipped to repel the invaders, and in 1959 Tibet’s religious and political leader, the Dalai Lama, was forced to escape over the border into India. Since then over 1.2 million Tibetans have been killed. Move than 250,000 Tibetans came to India at that time or in the period since then. They escape through the Himalayan mountains, usually in winter when snow, cold, and elevation make it difficult for Chinese troops to seal the border. The combination of the natural elements and border patrols make this a life threatening journey.

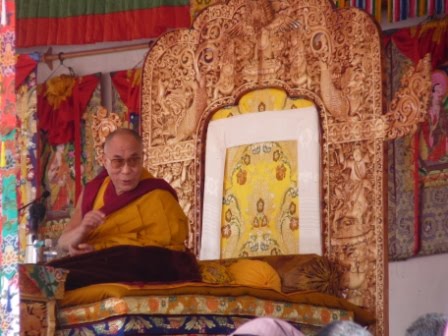

Here’s a picture of the Dalai Lama – yes, I took it! (Another story…)

McLeod Ganj is the home of the Tibetan government in exile, and they have a parliament that meets twice a year there. It is also the temporary home of the Dalai Lama, until he can once again return to Potala Palace in Lhasa. This year is the 50th anniversary of Tibetan exile. For many years cries of “Free Tibet” were heard in the Western World, but this cause has recently lost both momentum and fashionability, particularly as the Chinese have become a world economic powerhouse and other countries are hesitant to challenge them over human rights abuses.

Since they occupied Tibet, China has actively pursued their policy of “cultural revolution”. They have destroyed over 700 ancient Tibetan monasteries and Buddhist temples, including their libraries and works of art. Tibetan people were forced to change their customs, including personal things like cutting their long hair, and others as petty as switching from their traditional wooden bowls and spoons to another style. There has been a massive movement of Chinese citizens into Tibet so that now there are more Chinese in Lhasa than Tibetans. This dilutes the Tibetan population, watering down its culture and influence.

It is true that the Chinese have invested heavily in Tibet, building factories and schools, but these are Chinese factories and schools, and people who work or study there do so in a Chinese fashion (e.g. speaking the Chinese language, learning Chinese and not Tibetan history, etc.) Tibetans are subjected to strong prejudice making it difficult to find work, do business, or even go shopping, further encouraging them to suppress their language and traditional culture. Tibetan Buddhism, once the cornerstone of everything in Tibet, is no longer pervasive throughout society. Tibetans are under heavy government surveillance, and are regularly thrown into prison for being suspected of subversion, thereby suppressing even peaceful protest.

The combination of these things is resulting in the cultural genocide of the Tibetan people.

Here is an outrageous example of the vindictiveness of China’s control. Tibetans, like Hindus and Sikhs, believe in reincarnation, namely that after a person dies, he or she is reincarnated into the body of a newborn child. Given this, important people like the Dalai Lama can be identified in their next life after a long and complicated search process. The current Dalai Lama is in his fourteenth reincarnation. The Panchen Lama, the second highest Lama in Tibetan Buddhism, is in his tenth reincarnation and was born in 1989 in Tibet. He and the Dalai Lama have worked closely for centuries, with the Panchen Lama providing leadership during the period when the Dalai Lama dies, is reincarnated, and grows up. In 1995 the Panchen Lama was identified and confirmed by the Dalai Lama. Soon afterwards he and his family disappeared. The Chinese, in an effort to exercise control over Tibetan Buddhists and the Dalai Lama, took him away, and if he is still alive, are denying him the training in Buddhist philosophy that is necessary for him to resume the important and sacred position he has held in his nine previous lives. At the age of six, he became the world’s youngest political prisoner.

Here are some Tibetan Buddhist monks in India, including a group of novices.

While in McLeod Ganj, we volunteered in conversation classes with several people who had escaped from Tibet. Patrick met with a young man who had been in India for a few years. He is one of eighteen brothers and sisters. His brother and sister are both in prison in Tibet – he for raising a Tibetan flag, and she for communicating with her brother in India, the young man Patrick spoke with. They talked about a range of subjects, including some difficult ones that Patrick raised like, “Do you think that Tibetans can ever evict the Chinese without fighting?” His answer was surprising and appeared to demonstrate a much deeper understanding. He said that both Tibetans and Chinese wanted the same thing, “Happiness”. Patrick was surprised to hear that he intended to return to Tibet, and that he’d already tried once. His reasoning was that if the Tibetans departed, soon there would be no Tibet left to return to. People needed to stay there to maintain their culture and traditional way of life, to say nothing of their claim to their ancient land.

Diane met with two Tibetan Buddhist nuns, Lamdon (38) and Ngawang, both with shaved heads and wearing burgundy robes, and a young woman Sonam who shared a room with them. At first Diane was apprehensive, because she didn’t know what she was going to talk about for two hours with people who had come from extremely different cultures and had painful pasts. Initially the conversation started off with simple things like “Where are you from?”, “How long have you been traveling?”, etc. Lamdon did most of the talking, but her English wasn’t very good. Sonam shared a room with the two nuns, spoke better English and would bridge the communication gap for the nuns when needed. They made tea on an electric cook top that they had in their room.

Lamdon told the story of how she came to McLeod Ganj. After a brief show trial where she had no representation, Lamdon went to prison for two years in Tibet for being involved in a political protest. In prison she was beaten and her blood harvested. Prisoners in China undergo forced blood donations because rates of voluntary donation are low in China. When Diane heard this she started to cry, then Lamdon started to cry and got up and left the room. Ngawang told Diane, “Don’t cry” and offered her a tissue. Diane asked if the Lamdon would be OK, and she nodded. Diane was concerned that Lamdon felt that she had to tell her story, causing her re-live horrific past experiences. Eventually Lamdon returned and continued. After prison, she became a nun and studied in Tibet for two years. She decided to leave and walk to Nepal when the Chinese destroyed the monastery where she lived. Her family is all still in Tibet.

Sonam came to India with her aunt using a Chinese passport, something that most Tibetans cannot obtain. They are a people without citizenship. Their country no longer controls any territory and is not recognized by many other governments, to appease the Chinese. India offers them refugee status, but they are not Indian citizens. Sonam’s uncle is in prison in Tibet for making the film “Leaving Fear Behind” (www.leavingfearbehind.com)

The nuns both seemed genuinely pleased that Diane spent time with them, thanked her for coming, and asked her to come back again.

Speaking with Tibetan refugees directly affected by the theft of their country, systematic destruction of their culture, and mistreatment by the Chinese had a great impact on us. Surprisingly, like the young man Patrick spoke with, the

women didn’t appear to harbour malice toward the Chinese. In an amazingly Buddhist perspective, their outlook was of patience and empathy.

Any friend of Pat and Diane's is a friend of mine so any time the Dalai Lama wants to stay in Cloverdale – no problem!!

Diane you look beautiful and relaxed in that pic. And Pat ummmm…..you need some hair gel. hee-hee!

love, wandy

Another, take my breath away, story. You guys are meeting some pretty incredible people. I can't wait to hear the Dalai Lama story.

Nice hair Pat…Diane you are still as beautiful as ever….

Bev

I used to think that if I had to have a religion Buddism wouldn't be so bad. They seem to be so kind and forgiving. My trip to Thailand changed that thought, however.

Glad to hear you are still enjoying India. There is always great excitment when I see that a new blog has arrived.

Stay Safe, Love Linda and Gary

This comment has been removed by the author.

Diane agrees that Patrick needs hair gel. She tries to 'do' his hair occassionally, with little effect. We're hoping it'll calm down when it gets a little longer, but we've been saying that for months now.

Wanda – we'll send the Dalai Lama an invite to Surrey. Perhaps he can split his time between our two houses? Not sure where his bodyguards and the thousands of adoring Buddhists (like Richard Gere) will stay though…

Linda – yes, the Buddhist philosophy is appealing, more so than the other religions that we've experienced on this trip. It too is complicated by much history and ritual that tends to overwhelm the underlying message.